In the 21st century, technology change is happening on a global scale at warp speed. The business boom-and-bust cycle is shortening in duration and increasing in frequency. For example, two years ago Blackberry had over 50% of the handset market in the United States. Three days ago it announced layoffs of 40% of its workforce. Look at the table in this New York Times article to see how fast the phone handset market shifted. Similarly, the rate of worldwide tablet shipments are forecasted to top total PC shipments in the fourth quarter of 2013 and annually by 2015, according to IDC.

As Andy Stern, the founder and chairman of Intel said in a Wall Street Journal op-ed late in 2011: “The Agricultural Revolution was a roughly 3,000-year transition, the Industrial Revolution lasted 300 years, and this technology-led Global Revolution will take only 30-odd years. No single generation has witnessed so much change in a single lifetime.”

CHANGE THEORY

Why didn’t Blackberry change faster to defend its market position? In 1997, Clayton Christensen outlined in The Innovator’s Dilemma the seven major forces that slow or stop businesses from making changes that are in their long-term best interest.

- The pace of progress that markets demand may be different from the progress offered by technology.

- Disruptive innovation proposals that get the funding and manpower they require have a better chance of success than those that get less. (Duh!)

- Disruptive technology should be framed as a marketing challenge not a technical one.

- The capabilities of most organizations are far more specialized and context specific than most managers are inclined to believe . . . and are defined and refined by types of problems tackled in the past.

- The information required to make large and decisive investments in the face of disruptive technology often does not exist.

- It is not wise to adopt a blanket strategy to always be a leader, or always a follower. Market responses should vary based on sustaining vs. disruptive technologies.

- Successful companies populated by good managers have a genuinely hard time doing what does not fit their model for how to make money.

Since Christensen wrote his now-classic work over fifteen year ago, we know a lot more about what influences human change. As New York Times reporter Charles Duhigg reminds us in his engaging bestseller, The Power of Habit, half our days find us engaged in habitual behaviors driven by our brain chemistry. We know now that to adapt and change, humans need to have their social and emotional dimensions tapped, not just their intellect. But how?

CHANGE TACTICS

1. DIAGNOSIS: To mobilize change, the first step is to correctly diagnose root issues or frictions. What is holding back something from occurring naturally? Understanding the goal, role, or process nature of these issues will help you figure out how best to address them. Don’t be judgmental about the reasons people don’t want to do something, or don’t support a change. The first step it to find out why. Generally, listening is a much more effective way of gathering this information than talking!

2. MAP LEADERS AND INFLUENCERS: A company’s approach to change is often a reflection of its senior management: of the alchemy of who they are, what they are trying to do, their perspectives on the marketplace, and their appetite for risk and reward. You may have an obstructed view as you can’t possibly see everything that they see. But as a manager and change leader, you do probably see some things that they don’t! If you are trying to make something specific happen, you will want to make sure that key people with either power or influence are pulling with you, and certainly not against you. We have used the following process many times; it works because it addresses real concerns, and it leverages others’ skills and powers of persuasion.

Step #1: Visualize the Current State

- Imagine you are trying to pass a bill through Congress. (Perhaps not this Congress.)

- Seek to discover the individual positions of key leaders and map them on a scale of -2 (very against) to +2 (very supportive), with 0 being neutral. This is usually pretty easy to do by asking both directly and indirectly. Listen. Watch.

- Seek to find out the positions of those who are key influencers on the key decision makers and map those as well. These people may or may not have hierarchical power. If a key executive’s administrative assistant is a trusted influencer, then that person should be on your map.

- Review your “map.” How concentrated or broad is support? What are the common sticking points of those on the negative side of the map? Consider what there is full support for.

Step #2: Get to “Zero”

- To remove friction or “drag” on change, you need to get key individuals to neutral (zero), where they will no longer be resistant to the specific change you seek.

- For example, if a key player is a -2, but is influenced by three people who are +1, is there a way to get your +1s in a room with your -2 to help get him or her to neutral? (You may not need to physically be present for that conversation).

- Consider narrowing, broadening, or otherwise modifying your goal or approach to “get your negatives to zero” on the map. This isn’t giving up. This is how to generate momentum in the direction of your proposed change and gets your effort moving. By asking and receiving feedback, and then modifying your position, you show that you aren’t an ideologue, that you are listening, and that people can work with you.

- Be especially careful of leaders who say they support something, but don’t pull on the tug-of-war rope with you! This is particularly destructive for building momentum. If you sense that this is happening, go back to your mapping exercise and make sure you understand what this person is supportive of. What do they want to happen? How does it relate, if at all, to your plan? How could it relate?

TEMPLATE FOR MAPPING LEADERS AND INFLUENCERS

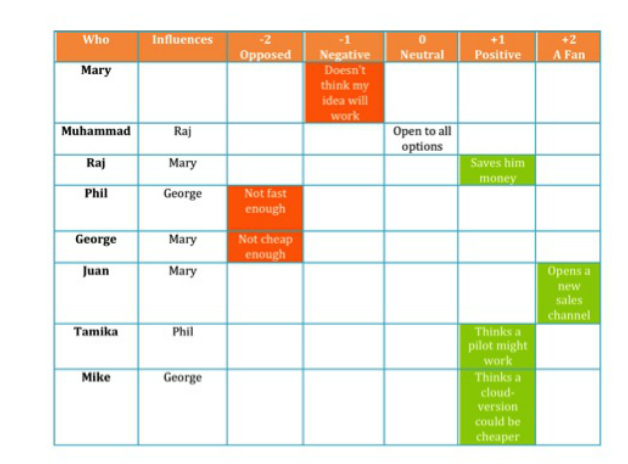

Instructions: List all the key players, their influencers, and where you think they “stand” on your idea — and why — from -2 to +2 as below. The purpose of the map is to help you visualize what you may need to do to get your idea moving forward. Be prepared to modify your idea –by taking a phased approach, for example — to help it “pass.”

In the example below, Mary, Phil, and George are opposed to the idea they have been presented with. Raj, Juan, Tamika, and Mike may be able to help you convince them, as they are more supportive, and then influence Mary, Phil, and George. But Muhammad won’t be of much help, because he is neutral and won’t likely be helpful in arguing your points. You may not need to “move” all three people, as most people don’t like to be a lone “no” vote.

Try this out and tell us what change you drove as a result in the comments box on our website or email it to us. We’d love to share your success!